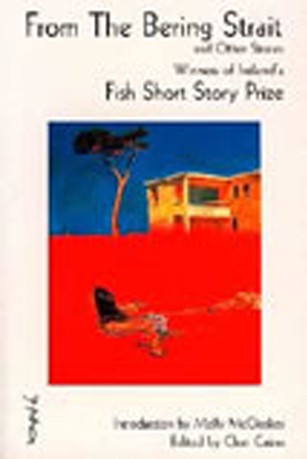

From the Bering Strait

ISBN: 0-9523522-7-3

Introduction by Molly McCloskey

In Frank O’Connor’s short story, News for the Church, Father Cassidy (known for his leniency) advises a young woman in his confessional: ‘It’s all the little temptations we don’t indulge in that give us true refinement.’ What a perfectly ambiguous piece of moral instruction. What music to our ears. What more could we ask for in the way of loopholes? For who is to say which are the little and which the not-so-little? How do you separate them? (Deliberation, reflection, a bit of time, but then not one of those keeps much company with temptation.) You could find yourself fudging, engaging in all sorts of intellectual gymnastics in order to allow yourself to call small big. On the other hand, if you really felt the need to go to such lengths, maybe that particular temptation wasn’t so little after all. Otherwise, why would you have bothered?

But wait a minute. Is it really the venials we need avoid? We thought those were the freebies, the forgivables, the ways of letting off steam, to keep us out of really big trouble. But then we’re talking about refinement here, not salvation. And whatabout refinement? It too seems a pretty relative term. What I call refined, you call retentive, or vice versa. Too much refinement and you tighten into preciousness, prudishness. You seize up. You’re no fun anymore. You can put people off with too much refinement, and that’ll pretty much take care of temptation for you.

So yes, as ethics, that piece of advice has its problems. But as aesthetics, and as a comment on the art of the short story itself, it seems perfectly apt. Because in the story, there’s only so much space, and you can’t have everything. Nor can you give it. Knowing what to hold back, what not to do, or say, is such a part of a story’s shaping. So that the story itself becomes a kind of enticement. Like being led by the hand to a particularly fascinating keyhole. But a keyhole, nonetheless. And right there, along with whatever slice of life we’ve glimpsed, are all the things we don’t know, or aren’t told, or haven’t fully understood. And that’s the beauty of it. That knowing everything would only spoil the view.

From the Bering Strait, by Gina Ochsner, is this year’s winning story. With its strange mixture of pained resignation, intimate involvement, and almost detached curiosity, it reads a little like a Letter from . . . , one of those daily missives we find in our newspapers, a communiqué penned from some exotic location in which unthinkable, often catastrophic, things are taking place. In this case, from where the ice caps have expanded, and the annual thaw, finally, has just stopped coming. There used to be ‘springs of wet snow and starlings, springs of impossible, violent blue skies’. But now, words and tears turn quickly to ice and, out of self-preservation, the inhabitants have ‘by unspoken consensus decided to try not to talk or sweat or bleed or cry . . . exposing any of our bodily fluids is a very dangerous thing to do. Still, we make mistakes.’

This story steps so lightly. Nothing is made overly much of, as though that kind of defeatism has set in where tragedies have come to seem commonplace. ‘There’s a funeral every other day, it seems, but nobody cries, of course.’ But despite its understatement, or perhaps because of it, it’s a beautifully powerful story.

To say that the story is a metaphor for some other kind of icing over – the days when, alone, we recall a past full of violent blue skies – is to suggest a certain contrivance which doesn’t exist. It’s just that the story is steeped in loss, in a way that is suggestive of more than its literal self. Children freeze to death, a friend dies drinking antifreeze and is found in a puddle of liquid (‘ . . . the striations of neon green and cobalt blue. If a peacock feather melted, maybe it would look like this . . . ’), but then there’s this business about the roses, as though if only the narrator and his wife can coax them forth through one more spring, the freeze will not have won.

But the roses don’t come, and his wife is succumbing to the lethal cold:

‘I think about what Dolores might be feeling, how it feels to slowly freeze, about how I am feeling. I think about how your heart still beats like it always did, but there is a tightness . . . Your heart is fighting to break free from the weight of the cold. And then your heart, over time, doesn’t fight as hard as it did the day before. And so it goes, and so it goes, until one day your heart just stops.’

Despite the story’s title, there is a timelessness and a placelessness to it that raises it out of itself. It’s wonderful.

In This is Art, a story by Maureen Aitken, the jauntiness, the gently flippancy, fail to mask the underlying melancholy. Nor are they meant to. The thirty-something narrator suffers from that premature weariness that comes from living in an overly ironic time. She works at an art institute, her boyfriend in a computer graphics firm – ‘creating mountains’ or putting cars on the moon. (‘They want them on the moon now. The earth isn’t good enough anymore.’) In this world of created surfaces – where fast-food joints stretch in the distance ‘like telephone poles, or stop signs’, repeating and repeating ‘until the eye could not know to see them anymore’ – she is trying hard to trust in something. In sincerity, or love, or maybe in trust itself. A mildly subversive act, in her world. This is a deceptively quiet story, punctuated by small epiphanies, moments of marvellous illumination.

Geraldine Taylor’s story, Etienne’s Tattoo, is a strange – and strangely compelling – tale which isn’t nearly as whimsical as its title suggests. It’s about two women friends, but it reads more like a love story, the narrator utterly besotted by Etienne, this ‘grotesque, repulsive and utterly beautiful’ woman. They meet in a motorway service station when Etienne says, ‘When men stare like you’re staring they’re wondering how it is with me . . . What’s your excuse, my friend?’

Dialogue carries a lot of weight in short stories. In good ones, it’s almost as though the characters know they’ve got ten seconds here and another ten there and if they choose their lines wisely, they can tell us everything that’s worth knowing about them. Etienne is peppered with just such dialogue. And the effect is that uncanny experience we can have when reading, of coming to know one character through the eyes of another – through the eyes of a narrator who’s never quite understood, but makes certain that we do.

In A Face in the Wallpaper, by Hugo Kelly, so much happens just off stage. Something’s wrong at home, something’s wrong with Mr Canning, too, who owns the local pub. The boy at the centre of the story seems a little disturbed; he sees faces in the wallpaper, a stuffed fox talks to him. The boy narrates in the second person: ‘The delta of meeting rivers on the cracked ceiling hold your attention. If you close your eyes you can hear their Amazonian roar. The diamonds that live in the carpet dance around you if you stare without blinking for long enough. The stairs to the attic is dark and there is a smell of old clothes and of another age that seems less bright than your own.’

The child’s perspective immerses us in a mental world where very little that’s seen is really understood. And when, in this case, whatever is seen is so disturbing, the second-person narration reminds us of how we can set about creating for ourselves an artificial distance from events, in order to survive them. As though it really were possible to be at one remove, to experience a story we’re in the midst of as though it were happening to someone else.

There’s humour in this collection too. Heard of a Band Called Mysterical?, by Mick Wood, is a very funny send-up of the rock’n’roll fantasy of an ill-fated garage band in its infancy. The narration reads like a deadpan, cinematic voice-over, which is utterly appropriate, as one of the band member’s favourite activities is imagining the documentaries that will one day be made about them. ‘Some years later (but not too many) as a moment in an MTV retrospective, and by way of poignant contrast, the ascent of these grotty steps is cut with shots of them mounting the stage in a vast stadium.’

The narrator shows little mercy, recounting every risible act, each self-conscious attempt at star quality, but somehow never losing his affection for his characters. There are wonderful walk-ons by con men and music industry has-beens. There is behind-the-scenes intrigue: before Mysterical has even played its first gig, egos are clashing, interlopers are muscling in. A teenage girl wanting to edge out the female lead singer, advises an infatuated band member: ‘All bands have their casualties. It’ll be in the first chapter of the autobiography, how you had to make the difficult but essential decision to lose that girl.’ She seems perfect for the band: no talent, but with an eye on posterity.

Pam Leeson’s story – the forces – is a story about the unsaid. It’s a record of missed opportunities and miscommunication, the pathos of signals utterly misread. What we actually read is a long dialogue consisting of everything two people (a couple on an outing) do not say to each other. When they do occasionally speak, it’s only to say the very opposite of what they’re thinking. The lack of capitalisation, the lack of punctuation, the very layout of the story, combine to heighten the sense that we are listening to two interior monologues impossibly in conversation with one another. The mild departures from logical progression or literal coherence, the quick ping-ponging of thoughts, produce in the reader a funny sense of vertigo, a dizzying disorientation that’s wholly appropriate to the subject matter. But the story has its own sense of order and as it progresses, swells towards a cumulative truth.

Every story in this book makes its own original way in the world. Knowing which are the telling moments, and showing them to us. Holding back when necessary. And as the narrator of the winning story casually remarks, ‘Sometimes, it’s the small things that really amaze me.’

Molly McCloskey, Sligo, 1999

Contents

From the Bering Strait by Gina Ochsner

Read this story in Short Stories to Read Online

A Game of Chess by Eithne Le Goff

Etienne’s Tattoo by Geraldine Taylor

Come to me, Sweet Dementia by Martin Malone

Reptiles by Patrick Sandes

the forces by Pam Leeson

Aqua Linda by Scott Lipanovich

Why I’ve Always Loved Fishmongers by Graham Mort

The Woman Who Swallowed The Book of Kells by Ian Wild

Sal by Derick Donahoe

The Imam’s Daughter by Shereen Pandit

Mr McInty’s Special Window by Rebecca Lisle

The Face in the Wallpaper by Hugo Kelly

This is Art by Maureen Aitken

Heard of a Band Called Mysterical? by Mick Wood

The No Thumb Hitch-Hiker by Sarah Weir

Life Assurance by Stella Galea

Wardrobe by Patrick O’Toole