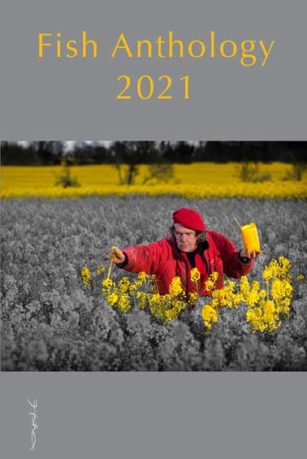

Fish Anthology 2021

ISBN: 978-0-9956200-4-9

SELECTED BY:

Emily Ruskovich ~ Short Story

Kathy Fish ~ Flash Fiction

Blake Morrison ~ Short Memoir

Billy Collins ~ Poetry

Read an excerpt from winning short story – A Correspondence by Mark Martin

Read winning flash story – Both On and Off by Jack Barker-Clark

Read an excerpt from winning memoir – Blood and Roses by Mary E Black

Read winning poem – Letter to Dowsie, from Roethke in Ireland by Greg Rappleye

Introductory Note

by Clem Cairns

Well, another strange year goes by; one more like that and it won’t seem so strange anymore. Whatever hardships and grief the pandemic has visited upon us, it has also bestowed on some a certain amount of opportunity. Writers everywhere have used the time freed up by the lack of normal activity to write, and we are gratified that so many have sent their work to Fish.

Emily Ruskovich, Blake Morrison, Kathy Fish and Billy Collins judged the Short Story, Short Memoir, Flash Fiction and Poetry Prizes respectively. It is not an easy task, so my deep gratitude to them for their time, for their interest in supporting aspiring writers, and for their wisdom.

To the 40 writers and poets in the following pages – congratulations! The quality of the work in this Anthology is astonishing.

And to those many talented writers who almost made it in, I hope that your work will find the light of day in another publication or a future Fish one.

And to the readers of this Anthology, I hope you are transported by story, memoir and poem. That you might, in the words of Billy Collins,

……… water-ski

across the surface (of a poem)

waving at the author’s name on the shore

Contents

SHORT STORIES |

|

|

A Correspondence |

Mark Martin |

|

Methane |

Pavle Miha |

|

The Fisherman |

Chris Weldon |

|

Aleksandr |

Amanda Huggins |

|

The Etymology of a Sword Swallower |

K Lockwood Jefford |

|

How to Accept the Lunar Landing |

Nicole Olweean |

|

Duck Egg Blue |

Fiona Ennis |

|

OMG Winn Handler Moved Next Door! |

Lesley Bannatyne |

|

Connemara Salmon |

Kathy MacGloin |

|

Rick and Molly Drink |

Giles Newington |

|

FLASH FICTION |

|

|

Both On and Off |

Jack Barker-Clark |

|

Cataracts and Dogberries |

Shey Marque |

|

Ouija |

Alexandra Blogier |

|

Lion |

Kirsty Seymour-Ure |

|

Desert |

Roland Leach |

|

Top Ten Reasons Why Pied-Noirs are Good at Packing Suitcases |

Laurence Gea |

|

The Day Amy Kinona Became Invisible |

Sharma Taylor |

|

Skeleton in the Cupboard |

Katherine Powlett |

|

What My Parents Were Wearing When She Decided Not to Keep Me |

Shoshauna Shy |

|

Ursula Sits |

Karenlee Thompson |

|

SHORT MEMOIRS |

|

|

Blood and Roses |

Mary E Black |

|

Becoming |

Hannah Persaud |

|

Dreams of Foreign Cities |

Martha G Wiseman |

|

Schmaltz |

Francesca Humphreys |

|

Broken Lines |

Mary Brown |

|

Fissure |

Ellyn Gelman |

|

Before the Dark Hour of Reason |

Kevin Acott |

|

Borderline Insanity |

Anthony Dew |

|

Dancing with Parkinson’s |

Leslie Mapp |

|

I have my suspicions about that Dachshund |

Alice Jolly |

|

POETRY |

|

|

Letter to Dowsie, from Roethke in Ireland |

Greg Rappleye |

|

Chemo |

Matt Hohner |

|

Don’t rush to clean her room |

Pippa Gough |

|

The Rowan Berries of Winter |

Phillip Crymble |

|

Ode to Ignorance |

Michael Lavers |

|

Swift Departure |

Will Ingrams |

|

December Sunlight by Harry Nisbet, 1919, Oil on Canvas |

Alice Twemlow |

|

First Time |

Maureen Boyle |

|

Story of a Sister whose Brother lost his Hand to the Buzz Saw |

Victoria Walvis |

|

The Breakup

|

Partridge Boswell |

A Correspondence

by Mark Martin

Morgan looked down as something slipped from the hardback in her hand, distracting her from Andrew. The bookshop where the two of them worked had closed for the day, and she was unpacking boxes of second-hand stock. A handsome young man, radiating impatience, Andrew held open the front door, a peach sunset framing his face.

‘Come on!’ he said. ‘There’s not much of summer left, let’s go have a drink on the green.’

The ranked spines on the bookshelves, Andrew himself — gorgeous in semi-profile, one foot out the door — and the mysterious boxes conspired to bring about in Morgan an unexpected sense of being intensely present. It was a realization, physical as much as intellectual, that she, approaching her last year of university, having chosen to remain in her college town over the holiday, was a young woman of potential in a world of possibilities. She was surrounded by mundane objects that, if caught at the right angle by a receptive intelligence, were full of charm. Outside, beyond the shop window, the setting sun was reinventing abstract impressionism. And in pleasant counterpoint to all this, here was a young man, smarter and better-looking than was reasonable to expect, practically begging her to join him for a drink.

‘There’s no time-and-a-half if you stay late,’ continued Andrew, frustration scoring his voice. ‘There’s more to life than you’ll find in books, you know.’

‘I’m going to work a bit longer,’ she said, abruptly making up her mind.

‘Suit yourself. Text me if you come to your senses.’

Both On and Off

by Jack Barker-Clark

On the phone to your daughter all winter. On the power of attorney. On cloud cuckoo land. On the canal boat you once owned. On bravery. On ignominy. On trial. On fresh grapes. On the occasion of your birthday. On call if you need us. On amplification. On overreaction. On hold with the doctors. On display for one month only. On our best-case scenario. Onwards and upwards. On lovely shiny wet new grapes.

On modern medicine. On the contrary. On the one hand not so bad. On the other hand terminal. On assisted living. On your head be it. On the bedside table, there, next to your reading glasses. On increasing medication. On a tour of hospitals, West Yorkshire, the surrounding Humber. On the formal bed, writing down what the doctor had said. On dyschronometriaand cerebellar lesions. On lovely shiny wet new grapes.

On the ward. On the pillows inmates rest on. On-demand westerns. On John Wayne. On horseback. On purpose. On the bathroom floor with the shower gel. On the bathroom floor with the shower gel following a stroke. On disturbing volcanic dreams now. On canal boats choked with weeds. On holiday in 1972. On ghost trains. On beach towels. On lovely shiny wet new grapes.

On average twenty beats per minute. On life support. On your own. On top of the breadbin. On all sides surrounded. On the way. On the beach with Eleanor. On the borderlands. On the grass slopes. On and on. On Wednesday the 20thMarch. On and on, and then suddenly off.

On behalf of those who knew him. On behalf of those who knew him best. On behalf of his grandson, unable to attend. On the TransPennine Express writing letters to his grandad who had died.

Blood and Roses

by Mary E Black

I was eleven years old when the Troubles started in 1969, a civil conflict fuelled by bad blood between two ethno-nationalist tribes. A book I will keep until the end of my days is ‘Lost Lives’ which tells the individual stories of the 3,637 who died over three decades. I know some of those names – Northern Ireland is a small place. Another 100,000 were wounded: shot, blasted by bombs, knee-capped in punishment shootings and beatings. As a doctor, from a family of doctors, I count the Troubles in blood. Yet, of the countless units of blood transfused during those years, we have kept no ledger.

I grew up in Lambeg, a staunchly Protestant village south of Belfast. My Catholic family comes from Antrim on my father’s side, with a three-generation excursion to Scotland; Cork on my mother’s side, with a family myth of no intermarriage with others for the last 400 years. Moving Hearts, an Irish Folk rock band from my youth, sang:

‘Once upon a time there was, Irish ways and Irish laws

Villages of Irish Blood, awaking to the morning, awaking to the morning.’

Letter to Dowsie, from Roethke in Ireland

by Greg Rappleye

Driven mad by channel wrack and fresh sprats in bad oil,

sobbing on the oyster dock, at lowest tide I was

rowed to the mail boat by a barefoot Carmelite,

then lugged ashore at Cleggan and poured into the back

of a Singer sedan. I swore I’d suppress my “affect”

for a splash on our way to the bughouse,

and the good padre, having tippled with me

in those dicey island days, found nothing against the faith

in that. He meted out Kilbeggan’s every ten miles

or-so, toasting each chosen apostle, excluding the Iscariot,

but counting Matthias and Paul. As single-pot prodigal,

I’ve found an easier, softer way: drinking cold buttermilk,

noshing stewed apples and mealy fishcakes

with the daft nuns and my attending physician,

a kindly man who is the spitball image of Barry Fitzgerald.

Walrus-like, I’ve wallowed in the hydro baths

as in our famous days at Mercywood, and thanks

to my trans-Atlantic laurels, my benzo-calm

and affable demeanor, I’m driven to a public house

on seisiún nights aboard the moron-bus, and allowed

two stiff drinks and the recitation of a poem.

It’s grand to hush the fiddles and part a cloud of pipe smoke,

led through the tavern door by four orderlies in white,

as if I’m blind O’Carolan, stumbled home at last,

escorted by that squadroon of virtuous angels

by which minor deities are ushered into the world.

On the wall chart of temperaments, mine approaches a shaker

of dry martinis—sanguine with ice and three drops of melancholic.

Dowsie, when did you last climb a honeysuckle trellis?

When did you last scurry through an asylum greenhouse,

tripping over clay pots and hashing your knees?

I imagine you now as sea-lioness, sleek and black,

your most clever pup dropped carelessly,

left to gorge on red dulse in a midnight sea

and you, shrieking all those long tumultuous hours

atop a granite rock, eelgrass wilding beyond you in the surf.