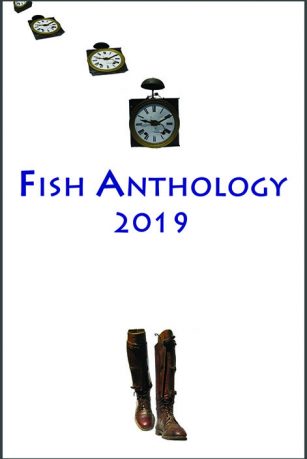

Fish Anthology 2019

SELECTED BY:

Mia Gallagher ~ Short Story

Pamela Painter ~ Flash Fiction

Chrissie Gittins ~ Short Memoir

Billy Collins ~ Poetry

Read an excerpt from winning short story –Wakkanai Station by Richard Lambert

Read winning flash story – Teavarran by Louise Swingler

Read an excerpt from winning memoir – Fejira // to cross by Bairbre Flood

Read winning poem –Not My Michael Furey by A M Cousins

Introduction

by Clem Cairns

This anthology contains the winning entries from the Fish Writing Prizes: Short Story, Flash Fiction, Short Memoir and Poetry, that were judged by Mia Gallagher, Pamela Painter, Chrissie Gittins and Billy Collins respectively. I thank them for their time, interest and wisdom.

We are in ‘interesting times’. Usually this means unpredictability, uncertainty and fear, to nations and to individuals. We see how countries react through the news media, with political leaders thrashing about like half-blinded kids in an unsupervised playground. For most of us, passing remarks over a cup of coffee or pint of beer satiates our appetite for reflection. But then there are the miners, the artists of word and tint, who burrow and chip at the edges of our hopes and shadows to try to navigate the landscape of the deep and dark places of the psyche. Writing is a profoundly subversive activity. A writer is a pearl diver and an astronaut and as both he takes risks. She explores the places where, as Heaney wrote, one can ‘catch the heart off guard, and blow it open’. It is the battle line where, in Leonard Cohen’s words, ‘the dreamers ride against the men of action’ (and we hope, of course, to ‘see the men of action falling back’).

An anthology like this one can provide a glimpse, a snapshot of the fringes of the world we live in, for the contributions come from all over the globe. They have, like the strongest salmon made it upstream through the selection processes of the Fish competitions and are residing in the still waters of this anthology. They are to be applauded for their endeavours. I hope that publication in this anthology is a standing ovation.

Contents

SHORT STORIES |

|

|

Wakkanai Station |

Richard Lambert |

|

Owl Eyes |

Mary Brown |

|

No Alternative |

Camilla Macpherson |

|

In Memoriam |

Joshua Davis |

|

Lukey |

Peter W Bishop |

|

Yvonne, Yvonne |

Linda Fennelly |

|

You were One of Us |

Mary Brown |

|

The Woodpusher |

Martin Keating |

|

Three Bodies |

Peter-Adrian Altini |

|

L is for Laura |

Tom Billings |

|

FLASH FICTION |

|

|

Teavarran |

Louise Swingler |

|

Micromanagement |

Jim Fay |

|

Seeing Stars, 1933 |

Gail Anderson |

|

Metamorphoses |

Deborah Appleton |

|

Vigil |

Berta Money |

|

Down Mexico Way |

David Horn |

|

Bashful Becomes an Outlaw and Laments the Marriage of a Close Friend |

Debra Bokur |

|

Mr Splendiferous and the Shadows in the Alley |

Debra Bokur |

|

Zodiac |

David Rhymes |

|

Toby |

K J Howard |

|

SHORT MEMOIRS |

|

|

Fejira // to cross |

Bairbre Flood |

|

In This House |

Nicola Keller |

|

Nebraska |

Ceilidh Michelle |

|

Magnum, Jeroboam, Rehoboam, Methuselah |

Jupiter Jones |

|

The Publican’s Daughter |

Wendy Breckon |

|

Trespass |

Gail Anderson |

|

Ginger |

Virginia (Ginger) Mortenson |

|

Hot and Cold Tar |

Aidan Hynes |

|

Between Joy and Sorrow: A Journey of the Hands |

David Francis |

|

Remembrance of Old Certainties |

Michael G Casey |

|

POETRY |

|

|

Not My Michael Furey |

A M Cousins |

|

The Morning I Read Yesterday’s ‘Daily Mirror’ |

Stephen de Búrca |

|

Rehearsals |

Colette Tennant |

|

Tequila Sunrise? |

John Michael Ruskovich |

|

Sugar Kelp |

Judith Janoo |

|

Kindling |

kerry rawlinson |

|

No Results for that Place |

Soma Mei Sheng Frazier |

|

Raiding My Dead Mother-in-Law’s Pharmaceuticals |

Alex Grant |

|

Capes and Daggers |

Leah C Stetson |

|

That One Time I Decided To Be All About Eschewing Obfuscation |

Alex Grant |

Wakkanai Station

by Richard Lambert

From my kitchen window I can see the station and beyond it the depot where arc lights come on with darkness and shine atop their towers so brightly that at night I often glimpse, gazing towards the sea, the train’s arrival. The train seems tiny from up here. Some mornings, standing at the window as I sip my coffee before work, I see it moving through the grey sleeping world and, if it is the engine with a broken headlamp, its remaining light twinkle in a way that reminds me of a person bearing a candle. But whenever I see the train into Wakkanai, whatever time of day it is and whatever time of year, I think of Mitsuko.

My first memory of Mitsuko – although I must have encountered her before – is connected to the mud track that skirted, and at one point entered, a clump of trees behind our schoolroom. In reality those trees occupied a tiny area but to us children they seemed a great and mysterious wilderness. Running down the track one break-time, I found her squatting at its edge, peering at something in the undergrowth. She had brown hair that fell, then as for all the time I knew her, around the side of her face. ‘What are you doing?’ I said. She did not reply. I squatted beside her and together we stared at a pile of leaves. We waited a long time and then, to my amazement, a bird hopped out. I was seven years old. It was forty years ago. I wonder, but do not know, if I would have waited so long for anyone else.

In Wakkanai Station

you bought me chocolate bars, my friend –

From Wakkanai Station

to Asahikawa

I ate sweet thoughts of you

* * *

It is dawn. I watch the grey curtains brighten slowly like an abstract canvas with a meaning I might come to understand. Eventually I get out of bed and open them. As usual for this time of year Wakkanai is covered by snow. From this window at the back of the flat, extends the ocean. It seethes, grey with white teeth – a strange companion. A band of cloud at the horizon merges slowly into the vast, faultless blue. Near the coast, birds fly rapidly. The smaller ones flicker like bits of paper.

Directly below, the caretaker has not yet cleared the overnight snow. But someone – probably the man who works for the shipping company – has already left for the day. Tyre tracks run from the garages and in one place a set of footprints circle where the driver must have stopped, got out, and walked round to the passenger door.

Father, you fished an ocean

of Sapporo and sake

with the vague nets of your mind.

Mother and I ate mackerel

our gills sucking on air

* * *

To the north, not quite visible, lies Karahuto, the island that Chekhov wrote about. The nationalists harangue us about Karahuto, calling for its return in the newspapers and from loudspeakers atop their black vans. Between here and Karahuto runs the Soya Strait through which container ships and oil freighters pass. Like the trains these ships are tiny and dream-like, although, whenever I have seen one close-up, moored in the harbour, they seem to be alive, like horses in a field.

Teavarran

by Louise Swingler

She can never believe how bright the gorse is, laid in great yellow arcs across the land. She breathes its coconut tang as she walks up the lane.

She can hear the gurgling veins of Scotland in the beck that runs in the ditch beside her. It’s twelve degrees here, cool after London’s twenty-four. The relief of it is a sensual chiding. She fits well here. Where does Thomas fit, though? You know I don’t do ‘green’, he says, whenever she asks him to come home with her.

She had wanted to come at Christmas, and in March.

A quad bike roars and she steps aside. Clumps of dock leaves are already growing back on the roughly-cropped verge. The one time he came, Thomas said these lanes ruined his suspension. He didn’t seem to realise how victorious this strip of tarmac is, checking the unstoppable push of the forest. But she knows it is but a temporary occupation. She enjoys this challenge to mankind’s arrogance.

Her father’s Highland cattle, flank deep, munch steadily through yellow rattle and buttercups. Two auburn calves are submerged like islands in an inland ocean of green, beige, purple, yellow. They raise their snubby noses, eyeing her. She thinks of Thomas, eyeing her as she left him at Luton Airport.

She looks across to the hills and the peaks behind them. The sky is a dull pearl, flat and quiet, and the morning mist has frozen into a row of frail tufts along the valley bottom, as if a steam train had recently departed.

She turns and stares into the calf’s swimming eyes, daring him.

‘If you don’t move before I blink, I’ll stay.’

Tick. Tock.

Her eyes begin to water. The calf remains still. Like a painting that Thomas can’t climb into. She blinks.

FEJIRA // to cross

by

Bairbre Flood

Someone offers to bring us to the beach and Bassam relaxes a little. It’s a sunny Spring day, and we can see all around the bay from the dunes; a Grecian colour scheme of intense blue and white. And a huge ferry boat gliding out to the UK, the floating steps and tiers just within eyeshot.

We talk about our favourite films, and the Iranian guys who’ve just managed to sail the English Channel in a dinghy.

When we get back the lads are getting ready to go try on the trucks. Ahmed is coughing so he takes a bottle of suppressant with him. He’d escaped as far as Egypt with his wife and children, then came alone to get to the UK, to send for them later. Months and months of trying, stuck in this shadow world.

‘Maybe tonight is the night for him,’ I said to Bassam as we wave them off.

‘Inshallah,’ said Bassam.

We light the candles in the shelter and Bassam blares out 1980’s power ballads on his iPhone. We sing along at the top of our voices. We never have to worry about waking the neighbours – they’ve got their own music on full blast and one of them is talking loudly on the phone in Urdu. We smoke and drink coffee until the early hours, and fall asleep to the gentle sound of scurrying rats on the shelter roof.

There’s no sign of the others for a few days and I drive Bassam mad.

‘Do you think they crossed?’ I keep asking, ‘Have you heard anything? How long do you think it’d be?’

‘Oh come on, stop!’ he said, ‘I don’t know!’

But the others didn’t make it, and arrived back in The Jungle. Ahmed got as far as the shelter door, collapsed and crawled onto the bottom bunk.

‘Are you ok?’ I ask.

He nods.

‘He’s crushed,’ Zain said, sitting down beside him.

‘He’s tried everything – even a fake passport didn’t work,’ Bassam said. ‘They spotted it immediately. It was a cheap copy, all he could afford. And now he’s nothing left – no chance, just to keep trying on the trucks, like this.’

Bassam gently wraps a blanket over him as he curls up on the bottom bunk and it seems like he’s disappearing. A hologram of himself, flickering under the blanket.

Or a birdsong slowly fading into the distance; each note distinct as it recedes.

Trying

The camp is getting more and more crowded, and a news crew is trying to get people to talk to them. A few Sudanese guys were getting lunch ready and they beckoned me over.

‘Come, come, eat something.’

‘Are you going to do an interview?’ I said, nodding at the crew setting up.

‘Why should I talk to them?’ one of them said. ‘Everyone knows what is going on in here!’

They pulled up a deckchair for me, and we dipped lumps of stale bread in a huge pot of chilli stew.

‘Everyone knows, but nothing changes,’ he said, looking at me intensely. ‘I’m sick of the journalists and the lawyers and politicians interviewing us, talking about us, giving us hope that people here in Europe will see – but nothing changes for us.’

‘We have to keep trying though?’ I heard the words ring out of my mouth. ‘Don’t we?’

‘We are trying’, he said. ‘We are trying to survive.’

‘Why don’t you claim here in France?’ I ask.

‘Look around you,’ he snorted. ‘Do you think they want us here? Do you think they would treat us like this if they wanted us here? In England maybe there is a better chance – maybe we will be welcome there.’

Not my Michael Furey

by A M Cousins

after James Joyce

While the girls watched the boys kick a ball

on a scuffed patch of earth behind the school,

I hid in the pre-fab hut that served

as library and refuge to the bashful.

There was shelter among chipboard shelves

where books offered solace to a child

weary of feigning interest in the chatter

of fashion and elusive boyfriends.

Here were English girls learning life-lessons

in progressive boarding-schools; young women

in the Chalet novels bravely dodged Nazis;

and Miss Heyer’s Regency heroines –

all sprigged muslin and beribboned bonnets –

were tastefully romanced by young bucks,

with chequered pasts and endless supplies

of starched cravats, who drove fast phaetons

and could tame a giddy, young filly

with one smouldering, masterful glance.

Sometimes I saw a boy near the Crime shelf –

barely thirteen, fingers and teeth nicotined

as a man’s. Once we talked and he held out

his yellow hands to show their tremor –

he suffered with the nerves – he liked a thriller,

a mystery to solve, Poirot was the best.

I preferred Miss Marple’s investigations

among the murdering genteel classes.

If I ever thought of him after that

I would have imagined him on his tractor,

the cab filled with smoke as he turned the sod

in neat lines on his father’s beet-field.

Some years later, my mother wrote me –

the priest had called his name at mass,

requested prayers for his soul’s repose;

she heard the talk at the chapel-gate –

he was found in the barn, no mystery

how his life of hardship came to an end.

He was not my Michael Furey, never

my tender young love but I think of him

often – in a makeshift library long ago,

wits pitted against a fictional detective

and a small, shy girl for company.