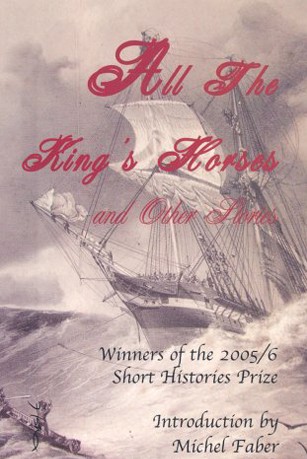

All the King’s Horses – Anthology of Historical Short Stories

ISBN: 0-9542586-4-9

From the Foreword, by Michel Faber

Most writers can identify the pitfalls of historical fiction wonderfully well. They can give you a list of temptations that must be resisted; indeed, some give lectures and produce manuals on the subject. Then, blind to their own advice, they fall head-first into the pit themselves.

The problem is, it’s not easy to write fiction set in bygone ages without doing all the things that good narrative sense tells us not to. Those who learn too much from the past are condemned to repeat it. That is, those who have carefully studied, eg, 17th century Flemish butchers as “background research” for their story are often condemned to tell us every little thing they’ve learned about butchery, the Flemings, and the 17th century in general. They may flatter themselves that this is precisely what they’ve avoided. They may assure us that what they show in the narrative is only the tip of the iceberg, and that the vast bulk of their research is actually submerged, unstated, implicit. They may speak disparagingly of those other historical writers who just can’t help pointing out period details twenty times per page. But then you start reading, and before you know it, you are inundated with information that the characters themselves would never remark upon. Illiterate peasants mention, in the course of unlikely conversations, what year it is and which king is on the throne. Pampered ladies who, in real life, would have regarded their servants the way we regard the electrical cord behind the fridge, feel honour-bound to describe everything their maids are doing. Everyone seems bizarrely compelled to analyse every aspect of their daily lives: the composition of their clothing, the contents of their food, the manufacture of virtually every object they touch. And, of course, every sentence spoken by everyone is stuffed with archaisms. Even Babylonian slaves and Vikings orate like pompous Victorians.

When writers of historical fiction do this, it’s not because they’ve gone mad. It’s because they fear – quite reasonably – that if they don’t keep reminding you of the past, you will get lazy and see the present. The present is our default setting. It is what we picture in the absence of specific information to the contrary. “A young man kissed his girlfriend in the street”: we see a modern man, a modern girl, a modern street, even a modern manner of kissing. Ancientness needs to be added, and kept topped up.

What, then, is the secret of a good historical story – a story that keeps us securely inside a bygone world, while not annoying us with constant reminders of where we’re supposed to be? How can an author recreate a past era in such a way that it isn’t a theme park?

For answers, I invite you to turn to ‘All The King’s Horses’, Jo Campbell’s winning story in the Short Histories Prize. In transporting us to a famous late-medieval battle and keeping us there, it does as much as it needs to, never more, never less. The beginning of the first line, “We came over the downs at dusk on the third day”, establishes a great deal in eleven simple words. The triple alliteration is reminiscent of Anglo-Saxon poetry, planting a subliminal suggestion of where we are in time. The use of “we” alerts us to the fact that this tale will convey the experience of more people than just an individual. The down-to-earth language (ten of the eleven words are monosyllables) signals that these are common folk. “On the third day” alludes to two previous days which we’ll never know about, because life moves on and the narrator is disinclined to waste time reminiscing. As the sentence opens up to acknowledge “the straggling lines of men coming from all directions to join in one long column”, we join the throng. We don’t know what’s going on and why we’re here, but then, neither do many of the soldiers. We’ve missed the start of this story, but if we fall into step, we’re expected to catch on.

Having established the tone and the pace, Campbell recognises the reader’s urgent need to see and hear the scene. “Around us on every side were points of light where soldiers already had their fires, and below us in the valley the flares of the shipyards and bonfires on the quays. We could hear the ring of the shipwrights’ hammers and the shouts of the sailors, and could see the masts, still bare, standing like saplings against the evening sky. Beyond the masts stretched a great darkness, with the evening star hanging above it. Now and then one or other of the fires would burn up for an instant, and by its light we could see the wrinkled surface of the water moving, moving.” Though only four sentences, it is the longest description in the story, if we define description as sensory scene-setting that is separate from character and action. Yet there is nothing gratuitous about it. Each of its components works very hard and very economically. It’s not just a vivid picture: we can divine quite a lot about what is going on. And it makes sense that our narrator would note all these things: he has never seen them before.

Then someone speaks. “Is that the sea?” asked young Wat; he had been longing to see it, but now he was almost too weary to look. I had been carrying him on my shoulders for the last few miles.” Here, so near to the outset of her story, Campbell manoeuvres the crucial emotions and themes into place: the vulnerable boy, the narrator who cares for him, the pitiless harshness of the endeavour, the ominous sense that no amount of promised glory can justify the sacrifice. All this, we absorb without fully knowing that we’ve taken it in. The story has us. We already understand it instinctively, even though we’ve barely entered its action.

I could write an in-depth analysis of what follows, every paragraph of it, and thus compose an introduction longer than the story itself. But the important thing to note, and to admire, is Campbell’s sound instincts for what needs saying and what should be left unsaid. Too often in historical fiction, characters seem aware of the momentousness of the events they’re embroiled in. Real life is seldom like that. People cope as best they can, living from minute to minute, performing the small tasks they’re given, trying to get along with whoever is closest. For many writers, in thrall to history books, the story of this battle is the story of King Henry V. But in Jo Campbell’s account, the king is never given a name, and the narrator hears of his prowess only second-hand. The battle as we experience it is fought by ordinary men – credible individuals whose ongoing concerns are food, warmth, a comfortable place to sleep. The name of a nearby village – Agincourt – is mentioned only once, in passing. That casual mention has power precisely because no particular import is placed on it.

Like all good stories about war, ‘All The King’s Men’ applies to all wars. Matter-of-fact references to bowmen and falchions remind us at judicious intervals of the medieval setting, but mainly we are enveloped in the perennial realities of soldiers killing and suffering as soldiers always do. This is an Iraq story as much as it is an Agincourt one. It is a passionate indictment of the damage that is done to men’s bodies, minds and morals by war, but there is no polemical posturing in it. The narrator fights well, and does what he must. At the end, he displays what he has become with no self-pity. He can’t change things now: his pain is History.

Not all of the stories in this anthology are quite as finely judged as ‘All The King’s Men’. A few display their research more than they need to. It’s no crime; some of the most celebrated, and best-selling, historical novels ever written might have benefited from more restraint. But each of the pieces here has been chosen for its excellence. And they are a delightfully varied assortment, ranging from deadpan simplicity to Baroque complication, raw horror to sophisticated humour, slice of life to clever artifice. More than usual for an anthology, this is a compendium of all the different ways that fiction can succeed.

Take Imogen Robertson’s ‘The Monkey’. It could scarcely be more different from ‘All The King’s Horses’ – except in its quality. Reading this wicked little tale of a dastardly Regency rake and his ill-fated purchase of a supernatural statuette, we never lose our awareness of being manipulated by an artificial construct, a neat device. Yet Robertson’s relish in screwing the plot tighter and tighter against her protesting villain is obvious; ‘The Monkey’ is the equal of Roald Dahl’s best revenge tales. And, crucially, Robertson takes care with her characterisation and her dialogue: the plot may be rigid as a steel trap, but there is nothing mechanical about the way these people behave and speak. This story has life. We suspend our disbelief for the sheer thrill of it and, more importantly, we care.

One of the mainstays of historical fiction is filling in the gaps of ill-documented lives of famous figures. Phil Jell slyly plays with this narrative tradition in his vividly evocative ‘Altarpiece’. A boy, known only as M, works as a lowly apprentice in the studio of a Renaissance painter. To the mingled alarm and wonder of the master, this “naïve, gangling, simple” lad produces work of sublime beauty, far superior to those of his employer. Thus, a murky drama of encouragement and abuse begins. And, up until the thought-provoking climax, the reader cannot help speculating on the true identity of the young genius … Similar territory is explored by Clare Girvan in ‘Titian’s Rose’, in which the painter recalls the infamous “Pietro Aretino, Tuscan, Venetian, writer, pornographer, poet, dramatist, womaniser, blackmailer and flatterer, libel-monger and man of letters, as unscrupulous as a stoat; my dearest friend.” This tale of lust, love and cuckoldry is narrated in old age, when memories of lost companionship and the nearness of death grant Titian the ability to forgive long-ago betrayals. Forgiveness is often portrayed as an act of grace, but Girvan shows us that it can be a matter of weary pragmatism, a conservation of energy by a battered old soul.

Feminist scholars have pointed out that history is often “his” story. Men have traditionally used the Law, social structures and business practice to disempower women. Sheila MacAvoy and Janette Walkinshaw explore these infuriating inequalities in contexts hundreds of years apart. MacAvoy’s ‘In The Valley of the Trinity’ takes us to the gold prospecting days of America’s wild west, where prostitutes struggle to survive in a society which, for all its frontier newness, is already rigged against them. This patiently crafted piece has the feel of well-documented, reconstructed fact, enlivened by prose of laconic eccentricity: “He had black eyes and whiskers the same.” Walkinshaw’s ‘Refugees’ is set many centuries earlier, when the Lord of Galloway dissolves a Dumfries priory and then casts the nuns out into the harshness of the workaday world. Here, too – as always when women are rendered destitute – prostitution enters the picture, but Walkinshaw handles her characters’ plight with tact and subtlety. Despite its medieval setting, this tale describes an ever-recurring journey; the nuns are refugees not just from the house of stone which they’d imagined “would stand forever”, but also from their former value systems and ideas of selfhood. History, as seen by most of the writers in this anthology, is not the building up of a dream, but its dissolution; not a journey to an exotic clime, but a diaspora from a disintegrating homeland.

Two pieces with the same title, ‘Russian Tea’, reached the competition’s final selection. Emma Darwin’s story, ‘Russian Tea’, is a bittersweet, understated portrait of Russian émigrés sleepwalking through a new life in London after their enforced flight from post-Tsarist Russia. Mikhael, groom to the aristocracy, dreams of noble St. Petersburg horses and, upon waking, takes the Piccadilly tube to the street pitch where he sells pencils, shoe polish and dominoes. His fall from the ranks of the exploiters to the exploited is sketched insightfully but without judgement, and his melancholy encounter with a fellow lost soul has just the right frisson of sexual tension. The opening lines of Mary Woodward’s ‘Russian Tea’ eloquently encapsulate the way memoir shades into fiction: “I remember the story. I think I remember the story.” The narrator toys with the idea of phoning her elderly aunt. After all, “she was there. It may have been more than sixty years ago but she has a good memory. She just might have the one or two details which will make it live. But then I pull back. No. She could say it wasn’t like that. Not the way you heard. It was this. It was so. And what she says might not help.” What follows is a self-confessedly unreliable but wholly convincing recreation of a World War II encounter, in which the tea of the title symbolises human potentials not often seen in this collection: generosity, honour, promises kept.

In tale after tale, the characters’ nobler instincts are undermined by the cruelty of larger forces they’re caught up in. And nowhere more so than in Hugo Kelly’s chilling tale of the Soviet gulag, ‘Vanishing Point’, in which Comrade Lesin from the Cultural-Educational Institute is given the task of motivating malnourished prisoners to dig a canal from the Baltic to the White Seas. Hiding his compassion under a veneer of cold indifference, he manages to achieve results while saving lives. But this is a world where any moral stand is fatally risky, so it’s entirely appropriate that Kelly’s narrator keeps us in the dark, maintaining an emotionally blank tone that only makes the horror of the scenario more potent. Like Jo Campbell, Hugo Kelly trusts his reader’s intelligence enough to let the story speak for itself, without trying to pump up the pathos.

All the tales I’ve discussed up till now, different as they are, are examples of conventional storytelling. Not so Judy Crozier’s ‘Dreamed A Dream’, a hallucinogenic vision of Lord Franklin’s expedition trapped in ice floes. Essentially plotless, as befits the marooned crew, it grips us solely with the poetry of its prose and the atmosphere of long-simmered madness. The lonely grandeur of frozen seas, and the unravelling morale of doomed sailors, have rarely inspired a meditation as sustained as Crozier’s, a vision of glacial delirium, full of remarkable lines like: “Our names are written with the finest of nibs on a map drawn in ice-white and blue.”

This is just one of the ways a story can succeed. This anthology offers ten. The past is here. Begin.

Michel Faber

2006

Contents

All the King’s Horses – Jo Campbell

Vanishing Point – Hugo Kelly

Altarpiece – Phil Jell

Russian Tea – Emma Darwin

Dreamed a Dream – Judy Crozier

Titian’s Rose – Clare Girvan

In the Valley of the Trinity – Sheila MacAvoy

The Monkey – Imogen Robertson

Refugees – Janette Walkinshaw

Russian Tea – Mary Woodward

N.B. The list doesn’t include a typographical error. Curiously, two very different stories with exactly the same title made it through to the final winning entries.